Location is everything, or so the saying goes. But that’s only partially true, and Indian country is living proof of that. Some of the most remote Tribal communities thrive thanks to off-the- beaten-path, destination-style resorts, tourism, utilizing natural resources, or by leveraging water rights in the arid southwest. Meanwhile, some tribes in populated cities may not be capitalizing on their full potential, like hiring staff with advanced financial acumen and efficiency skills, or marketing their in-house skilled talent pool by providing consulting services to other tribes or commercial businesses.

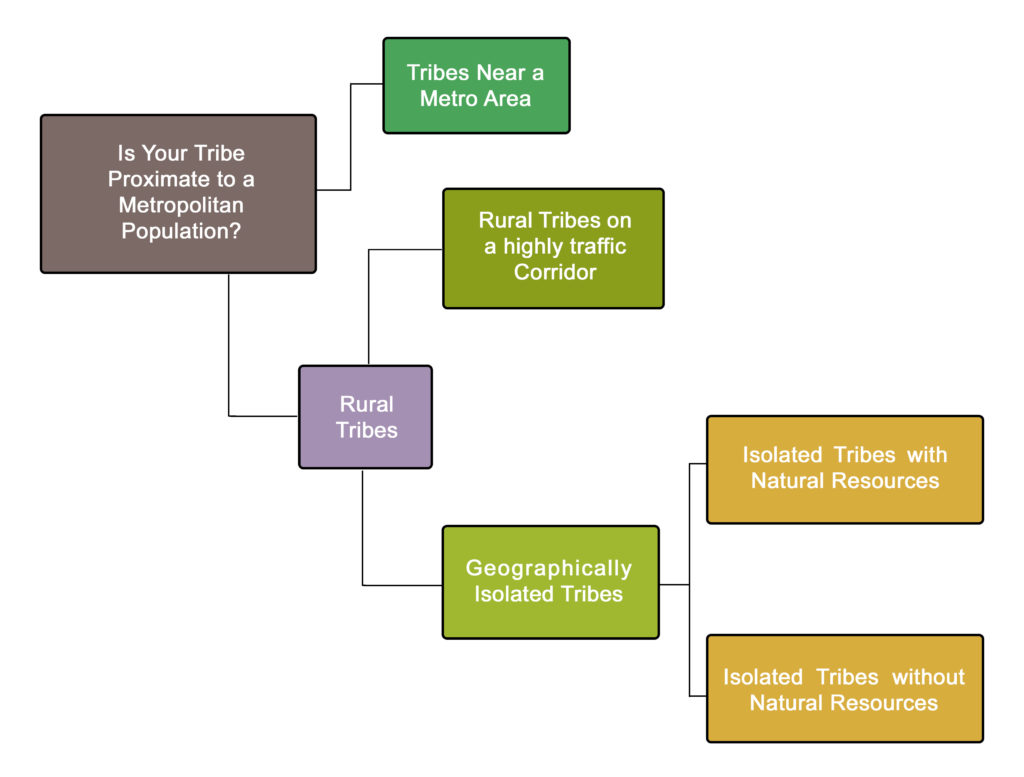

From large metroplexes to middle-of-nowhere America, tribes are both strengthened and limited by their location and economic geography. There are a few tricks of the trade for strategizing a big-picture, economic development plan, relative to where a tribe is situated on the map. Blue Stone has some insights, whether you are:

- A tribe near a metropolitan area

- A rural tribe on a high-traffic corridor

- An isolated tribe with natural resources

- An isolated tribe without natural resources

Below we lend some innovative perspectives based on first-hand experiences advising tribes, as well as approaches rooted in fundamental economic principles, applied to unique tribal situations.

Read on to learn more about capturing a bigger share of your city’s wallet through competitive advantage, leveraging economic “clusters,” honing in on growth industries, analyzing industry trends, conducting profitability assessments, eliminating “leakage,” and much more.

Evaluating Options

“Looking back, our advantage as a tribe was that we learned to look at what others were doing and see what worked and what hasn’t. We learned from their mistakes, as well as what they have done right.” (Ed Pigeon, Gun Lake)

As discussed in Part 2, the first step in a tribe’s diversification effort should be to assess the economic opportunities available to the tribe based on its particular location. The economic development opportunities on reservations that feature predominantly trust land are fundamentally similar to that of large, master-planned land-use programs. This means that in order to understand what’s economically possible, you have to understand the potential consumers, or customers, available given a tribe’s specific location. Naturally, there are multiple strategies that tribes can use to overcome their geographic limitations. For example, some tribes use a ‘destination’ or ‘resort’ model to attract customers from relatively distant locations for multiple-night stays in their casino. The key is to learn the potential opportunities a tribe can explore based on its particular location and economic geography, and then develop customized development strategies based on that reality.

Most tribes find themselves in one of two situations: They are either near a relatively large metropolitan population, in which case they likely have developed gaming ventures to attract nearby customers; or they find themselves in relatively rural, isolated locations, where gaming operations consequently are based on destination resort models or on capturing customers who travel through or near the reservation on major highways on their way from one metropolitan area to another. Tribes with land along a major highway or interstate are best situated, as they can still establish profitable gaming operations despite being relatively rural. Others find themselves in truly rural environments without easy access to major markets, and likely have small gaming operations typically frequented mostly by tribal members. At best, truly rural gaming tribes can build large destination resorts to which customers are willing to travel long distances and typically stay for multiple nights.

Determining which diversification path best suits a tribe’s particular needs depends in part on its geographical location. Opportunities available to a rural tribe tend to depend heavily on the size of its reservation and the natural resources it holds under trust. Tribes with little acreage tend to have to focus on creating service-oriented enterprises that do not require square footage. Comparatively, tribes with vast reservations often contain one or more marketable natural resources that can – if so chosen by tribal leaders – be leveraged for economic development purposes. While each tribe is unique – one can have both rural and urban attributes – it is helpful to break down possible economic development opportunity sets into four categories: Tribes Near a Metropolitan Area, Rural Tribes on High-traffic Corridors, Isolated Tribes with Natural Resources, and Isolated Tribes without Natural Resources.

The options for diversification differ depending on which category best describes a particular tribe’s situation. Recognizing that some tribes have multiple characteristics, let’s examine a few situations to better understand how the economic diversification opportunity sets for tribes are determined in each category.

The options for diversification differ depending on which category best describes a particular tribe’s situation. Recognizing that some tribes have multiple characteristics, let’s examine a few situations to better understand how the economic diversification opportunity sets for tribes are determined in each category.

Planning for Diversification: Tribes Near a Metropolitan Area

Expanding upon the three types of commercial locations outlined in the previous chart, a large part of planning for diversification depends on the degree of access to a metropolitan population that can supply customers for potential enterprises. Naturally, tribes near large metropolitan areas have a strong structural economic advantage, left to solve the straightforward challenge of capturing an adequate piece of the purchasing power, or share of the wallet, of the existing customer base located in those areas. This assumes that the tribal population in and of itself isn’t large enough to generate sufficient economic value, which is typically the case for most tribes that have a member population much smaller than a neighboring city.

While Tribes near a metropolitan area can pursue economic diversification with any strategy or set of strategies, it is most likely that the strategy with the most likelihood for success will be based on capturing the market potential of the nearby population. In many ways, this concept is similar to the logic that drives large gaming initiatives for tribes near metropolitan areas. Whether they are located in New England, California or the Southwest, the question for Tribes facing the diversification challenge is how to leverage this concept through enterprises other than gaming.

Utilizing some common academic frameworks and concepts from traditional economic development can help answer this question. The first is the concept of competitive advantage. Put simply, the idea is that any business or enterprise should focus its efforts on activities where it has a distinct advantage compared to its competitors. For example, because tribes have tax and regulatory advantages over neighboring non-tribal governments, they can create businesses that can make and/or sell products on reservation land cheaper to customers. As a result, customers looking to save money will leave the metropolitan area and drive to the reservation to purchase these goods. This phenomenon is common across the United States and serves as the basis for many tribal enterprises from gas stations to firework stands to smoke shops. The notion of competitive advantage predates gaming and is the economic basis for much of the growth of tribal enterprises in the pre-gaming era. Applying this concept in the post-gaming era presents tribes new diversification options where the same inherent competitive advantage applies.

The second theory that helps to illuminate the diversification options for tribes near metropolitan areas is the concept of economic “clusters.” This notion, now widely applied in economic development, is originally based on the work of Harvard Business School Professor Michael Porter, who first coined the term “Porter’s Five Forces” has for decades advocated the notion of competitive advantage and industry clusters. There are many different definitions of “clusters,” but all basically describe a collection of skillsets that are located in the same geographic area and have developed a collective capability or benefit that is greater than what they would each contribute if they operated independently. Examples of this are found all over modern life and range from the concept of shopping malls (stores located together attract more total customers than they each could separately) to the metropolitan area of Detroit (where suppliers and manufacturers are closely situated to reduce transport information sharing costs).

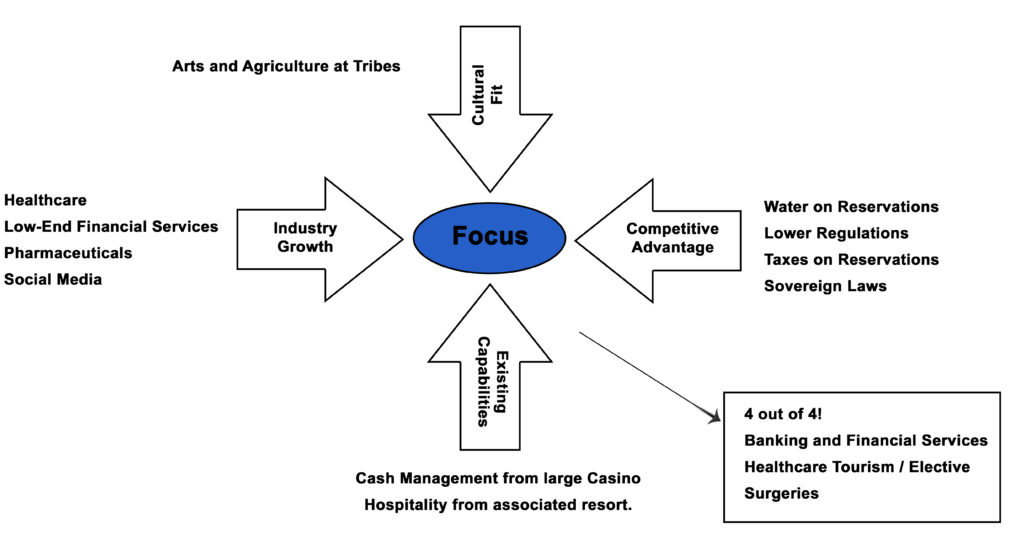

Combining the basic principles found in clustering and competitive advantage and applying them to Tribes Near Metropolitan Areas provides concrete, viable options for economic diversification. Consider the graph below developed for a gaming tribe with a casino and resort located New Mexico.

This model considers four particular criteria for diversification options. First, a tribe needs to consider whether the project is a good cultural fit. While acknowledging the primary focus of this book, Blue Stone Strategy Group always works with tribes to screen new business ideas through a cultural lens. For example, there may be particular aspects of a tribe’s culture or traditional practices that they would like to leverage economically, such as traditional foods or arts and crafts, such as with many of the Tribes in the Southwest. Conversely, a Tribe’s culture and core values might argue strongly against engaging in economic activities that contradict or endanger its culture and values. Examples of this include strong opposition to uranium mining on sensitive cultural sites.

The second, whether or not the industry is a growth industry. This is a simple initial screen that provides some macroeconomic development cushion to any project a tribe is considering. Diversifying into industries that are expanding as a whole will have a higher likelihood of succeeding in the overall economy, especially if the industry is a growth industry in the surrounding local economy. In this example growing industries in the area where highly focused around healthcare, pharmaceuticals.

The second, whether or not the industry is a growth industry. This is a simple initial screen that provides some macroeconomic development cushion to any project a tribe is considering. Diversifying into industries that are expanding as a whole will have a higher likelihood of succeeding in the overall economy, especially if the industry is a growth industry in the surrounding local economy. In this example growing industries in the area where highly focused around healthcare, pharmaceuticals.

Third, the capabilities that the tribe already has. This term will be used throughout this section in numerous concepts. Simply put, this consists of the skills that a tribe currently has – through its leaders, employees and potential employees. This can range from capabilities around land management and government administration to running large casinos. The capabilities, or skills, that are contained within the tribe and its enterprises can be far greater than is often given credit. As sovereign nations, but also as business owners, most gaming tribes have in a relatively short time acquired skills critical to operating a wide array of businesses. Whether it is accounting, marketing, management, financing, public relations or even public policy, most tribes with gaming enterprises have cultivated a strong reservoir of skill sets that can be leveraged and transitioned into other related businesses. In the Isleta example, the sheer size of the tribe’s casino required substantial and complex cash management, compliance and working capital management skills.

Fourth, consider the competitive advantage. In this example, the Tribe had access to water rights in the southwest where water rights carry substantial value. The “use it or lose it” provision with respect to those rights meant that the Tribe was heavily incentivized to put to use as much of its available water as possible to ensure that those rights were retained for future generations. Like most tribes, this example also included the standard set of tax and regulation requirements that were much lower than the neighboring metropolitan area.

In this example which considered competitive advantage, cultural fit, industry growth and existing tribal capabilities, two clear answers emerge as potential avenues for diversification: Healthcare tourism/elective surgeries and banking and financial services. Using this methodology, these two options pass the test in all four focus categories.

Banking and financial services stem from the fact that this Tribe’s casino operations are robust enough and they have been through enough project financing that it’s very likely they have internal skill sets – individuals with the requisite knowledge base and experience – to be able to expand into providing some form of financial services to the enterprise.

Managing the budget, cash flow and accounting of the casino operations requires staff to have an advanced level of financial acumen and information technology sophistication that can be leveraged in other enterprises. This may be as simple as insurance brokering or as complex as purchasing a local credit union or bank. Another option could be to start a payroll processing enterprise that first handles existing accounts for the casino and government but then extends to offer services off of the reservation to the nearby business community. We will explore this concept, known as “exporting internal functions,” further in subsequent chapters.

The second diversification option is based on Isleta’s operations management capabilities gained from running a resort coupled with a large demand for elective surgery in the nearby metropolitan area. “Healthcare tourism” refers to when individuals travel to another country specifically to obtain medical care.

Across the globe, private delivery of elective medical procedures has developed into a lucrative, high-growth industry. Thailand’s “star rated” hospital system caters to regional executives looking for extended-stay luxury accommodations to accompany cosmetic surgery and childbirth procedures. In the United States, hospitals such as Texas Children’s have substantial offerings for foreign nationals requiring a range of non-emergency services. Locally, for tribes, the bureaucracy and increasing costs of the United States healthcare system presents an opportunity to provide fee-for-service elective medical procedures in a convenient location offering full resort-style amenities to patients and their families.

These services often come with high-margin procedures and – when combined with an existing resort – primarily involve acquiring the appropriate medical staff and equipment. One example of this is “birthing centers,” which are increasingly popular in the United States and, depending on state law, can be staffed by a team of certified midwives. These facilities command high fees and provide a currently desired alternative for women who want more substantial support and enhanced accommodations compared to a home birth, but do not wish to have a hospital birth. This is just one example of the healthcare-related opportunities that Tribes Near a Metropolitan Area may have to create diverse streams of revenue aside from gaming by leveraging existing capabilities from gaming-related enterprises.

“Every tribe must have at least one person with business experience who is strategic, has critical thinking skills, understands the entire process and is able to see it from conception to completion. This means they have not only the vision, but also the attention to detail and analysis skills. They must be able to make timely decisions and have the ability to identify key critical decision points. ‘Go, no go’ determinations are critical.” (Lynn Malerba, Mohegan)

Planning for Diversification: Rural Tribes on High-Traffic Corridors

Many tribes around the country find themselves situated on a rural reservation that is not particularly near a metropolitan area, but is between two metropolitan areas with land very close if not adjacent to major highways. In these instances, the potential for diversification opportunities that should first be explored usually relate to the traffic that is flowing through or near the reservation. There are numerous examples of this, such as Acoma Pueblo located on both I-25 and historic Route 66 in New Mexico; the Gun Lake Tribe situated midway between between Grand Rapids and Kalamazoo, Michigan; and the many tribes located along I-5 in California.

In these situations, the first step to planning for diversification is to understand the customers that are literally driving past or through tribal lands: Who are they? How old are they? What do they like to buy? What needed services are not nearby? Why are they on the road? Etc. This is the basis for many tribal truck stop, convenience store, and casino variations. While some tribes moved quickly to capture this “passerby” market, others have yet to take full advantage. Those that have typically find that they capture a much more sizable “share of wallet” than can be generated by selling a tank of discounted gas. For example, let’s consider Blue Stone’s work with a Tribe in the Upper Midwest region.

This Tribe initially developed a casino and then began investigating what other ventures could generate revenue for the tribe. From an economic standpoint, it seemed logical to investigate diversification into a gas station given the proximity to the highway. However, like many tribes, leadership desired to have more than a few pumps offering discounted gas. They wanted to capture as many cars and trucks passing them as possible and as much share of wallet as they could. But generating a consensus among members to diversify beyond gaming proved to be an uphill climb.

According to its Tribal chairman, “Diversification is something most tribes strive to do. In our case just getting people to talk about diversification is a huge win for us.” To help achieve this, Blue Stone conducted on-site visits that included financial, market positioning and competitive profiling of eight convenience stores within the same market. Wholesale gasoline distribution and supply points were identified and combined with customer behavior research to determine pricing. Blue Stone also provided an extensive general convenience store industry trends analysis. This information was then used to develop financial models for a potential Store.

The overall convenience store industry has displayed remarkable stability despite volatile gas prices, and has experienced steady increases of 1-2 percent per year for the last 10 years. The number of stations owned by independent (non-chain) operators has increased over the last decade due to increasing gas prices and the increasing availability of reliable quality, unbranded fuel.

Traditionally, store performance is comprised of the three largest sales categories: Gas, cigarettes, and alcohol. Gas sales provide revenue and volume at low margins, in-store sales offer higher margins (from 30 to 40 percent) that drive bottom-line profit. Candy, chips, soda and coffee provide additional profit centers for convenience store operations. Car washes cost $200,000 – $300,000, yet they generate between 500 and 1,100 percent profit margin on a per-cost basis. In recent years the primary area of innovation for store operations is the offering of food service: fresh foods (pre prepared sandwiches, salads, etc.), hot food offerings (burgers, burritos, hot sandwiches, etc.), and franchise food services. This area has been the fastest growing segment of in-store profit for the past several years.

From their perspective, the advantage of being adjacent to a highway translated into an average of 30,000 vehicles passing through each day, with an unusually high percentage of truck traffic due to the large furniture manufacturing nearby. Traffic data also indicated a commuter pattern with spikes just before and after working hours and a significant drop in traffic on the weekends. Some variation occurred during summer, when boating/recreation traffic increased on the weekend.

Both of these factors were offset by steady casino traffic. The casino tallied over 150,000 players club customers in the last 12 months, which helped to offset the ebb and flow of the traffic patterns and ensure a regular flow of customers. Their location also offered some obvious strengths: highway visibility and a dedicated exit, proximity to the casino, and a lack of direct, immediate competition. Blue Stone evaluated eight area competitors and generated estimates for volume, pricing, and profit for each store. Among these eight, stations exist two miles away in either direction on the highway, and less than one mile away on a nearby road. However, none of these are able to offer comparable pricing or the added bonus of an adjoining casino.

Like many tribes, their situation also offered pricing and tax advantages. Competitors’ pricing was highly variable. There was as much as a thirty-cent differential between the highest and lowest in the area. This presented an opportunity for the Tribe’s operation to compete within a wide range of prices; however, it also presented a challenge in that management had to monitor area prices and adjust based on the market dynamics. Pricing on a cost-plus model could be detrimental to volume. They can keep two thirds of the six-percent sales tax (below $5 million in sales; half of the 50 percent of the six-percent sales tax above $5 million) applicable to all convenience store items. Because the tax dollars go to the Tribe, they can be used as pricing leverage against competitors. Based on the current compact with the state, the Tribe does not have the ability to charge tribal gas or cigarette taxes in lieu of state taxes.

Given this situation, there was a strong option for diversification with a restaurant and convenience store combination that, based on conservative calculations, would produce a minimum annual profit of $700,000, would cost less than $5 million to build, and could be completed in fewer than 180 days. A travel plaza and truck center, it would be located across the street from the casino and would be equipped with ten gasoline pumps (or twenty fueling positions) with a separate eight diesel pumps (or sixteen fueling positions) catering to semi-trucks. The store would offer mid-range trucking options (increased seating and merchandise options, parking spaces, and showers), but would not be a full-service (repair, trucking gear, etc.) operation. The concept would include a 2,000 foot white box shell for a nationally branded QSR (fast food) and have the casino either run the operations or negotiate a lease. Operations also would also be integrated, as the Travel and Truck Center and the casino engaging in cross-marketing, with customers being able to redeem casino player’s club points at the Travel and Truck Center.

This example illustrates a classic example of diversification for a rural tribe located close to a roadway with high-volume traffic. With a relatively small investment, they can secure a strong, stable, cash flow-positive enterprise and tax revenue stream for decades to come.

“Gaming revenue is everything. It’s the revenue you create with gaming that sets the stage for the future,” says their Tribal leader. “A lot of tribes look at diversification that is gaming where construction companies launch goods and services that could be a spinoff of gaming; that’s how tribes have started.”

Many tribes in that particular region intuitively understand this opportunity. However, only through careful planning and systematic research of the appropriate economic development concept or concepts designed to capture the most customers and the most dollars from those customers can tribes can realize far greater financial benefits. What customers will pull off the road and pay for varies widely from situation to situation. For commuters, tribes often focus convenience store enterprises on frequent fueling programs and offer takeout hot food items for working families coming home to children. For truckers, the focus is much different, based on extended dining options and amenities such as showers, truck washes and sometimes entertainment options. By combining traditional competitive advantages such as fuel taxes with a focus on a thoughtful business plan, tribes can take full advantage of their location near high-traffic corridors.

“Tribes need to have a bigger view of what is possible out there. Don’t restrict yourself to the resources that you have right now – develop other resources and support systems like roads, railheads, bridges. You have to think bigger, and have the confidence that you can go out and develop a framework for how to get things done.” (Mel Tonasket, Colville)

Planning for Diversification: Isolated Tribes with Natural Resources

Many tribes, particularly in the western United States and in Maine, have rural, isolated reservations that are not near any major population centers or high-traffic corridors. Some of these reservations have natural resources in abundance, which provide a natural starting point for options for diversification beyond gaming. In these situations, tribes typically struggle with gaming in general because of a lack of access to a large enough population capable of providing enough casino patrons to make gaming profitable.

To overcome this challenge, in some cases tribes develop ‘destination resorts’ that seek to attract casino patrons from long distances for multiple-day stays. When combined with marketing for small-scale conferences and corporate ‘retreats,’ this approach can prove to be successful. For example, pueblos in New Mexico have developed modestly successful models based on this approach.

As tribes in this situation look beyond gaming, reservation natural resources are likely the first place to capitalize on economic opportunities.

For tribes in the northwest and Maine, this often means timber, agriculture and fishery enterprises. For some tribes where it is culturally acceptable, opportunities in the extractive industries, such as coal and natural gas, present prime opportunities for economic diversification. In the arid southwest, natural resource opportunities also can come in the form of water rights. Take for example the a Tribe in Arizona, which has leveraged their ground-breaking water rights and available desert reservation land into one of that state’s largest farms.

Over time, the Tribe developed an economic diversification strategy to utilize their most valuable natural asset, 85,000 afa of permanent water supply. Covering 18,000 acres, it produces almost $20 million in revenue and $10 million in returns to the tribe annually from alfalfa, barley, potatoes, pecans, milo and corn silage. Their tribal farming facility professionally manages its portfolio mix optimizing across numerous factors, including: local demand, price stability, water usage, ease of cultivation, efficiency in watering, and fertilizer timing. Farm managers also hedge the farms’ commodity exposure to reduce overall variability and risk. By leverage their water rights into a profitable enterprise, they have illuminated one viable path for relatively rural and isolated tribes to diversify beyond gaming.

Blue Stone Strategy Group also worked with the tribal council to evaluate and conduct a business development and profitability assessment to determine whether to acquire the a local golf course. The geographic location of the golf course placed it within the boundaries of the Community’s original land base and was now adjacent to its current land base, providing them a significant cultural incentive to purchase the business. The Community envisioned owning and operating the course in tandem with its adjacent gaming facility, targeting casino patrons to “stay and play,” thus creating a destination resort.

The initial evaluation revealed that the course had a good reputation; however, it was losing money annually to the tune of $300,000. Its operations were in a critical state, and the facility and equipment were run down and in need of significant maintenance, which would require investments of more than $500,000 if the course was going to compete in the regional market. Blue Stone conducted a comparative rate schedule study identifying inefficiencies and opportunities to raise the midweek rates to help close the deficit.

During the preliminary financial review of the facility, it was determined that the tribe would at a minimum have to increase to 100 rounds per week, charge new players $50.00 per person for green fees to offset the losses, and nearly double the room capacity at the Casino Resort to provide lodging to the additional players. In addition, the quality of the food and beverage menu and services was below industry standards and required a transformation. It was determined that increasing the overall food quality and selection would nearly triple their income from foods and beverages. Operational improvement recommendations were made to improve inventory control and financial operations and also standardize pricing.

Upon concluding its assessment, Blue Stone recommended to the Tribal Council that the Community create a cost savings by eliminating the management contract and have the operation of the facility be conducted by the tribe, that it revise its compensation structure to represent the regional market, and that it utilize a national reservation system. The recommendations that they ultimately implemented resulted in increased revenues and reduced expenses, allowing financial pro forma to move from an operation loss of more than $300,500 to a forecasted operating profit of more than $330,000. Additional casino and hotel revenues also were generated based on the “stay-and-play” concept. Tribal employment also increased, with the golf course alone creating an additional 20 jobs. The strategy to create a stay-and-play environment by creating adjacent amenities for individuals visiting the location created a positive impact to the overall community.

In addition to these efforts, the Community, with Blue Stone’s assistance, conducted an assessment of its community store and an efficiency assessment of an improvement project for its farm business. The Community had a convenience store that sold grocery items located on their tribal lands. The facility was in very poor condition and required extensive maintenance. Unsanitary conditions, spoiled goods, limited product offerings, poor pricing and high turnover rates were all issues plaguing the facility, making it impossible for the business to serve quality products in the community’s best interest or meet industry standards. The facility was located nearly two miles off of the main highway near tribal member housing. Community members did not want an influx of non-tribal members coming into their residential area.

The Community wanted to explore whether it made economic sense to upgrade the existing facility or build a new facility that could expand upon what the current store offered. It was specifically interested in the costs and benefits, investments, and capital requirements associated with each. The facility provided a limited number of jobs, fuel, produce, and other goods to the community.

Blue Stone, in cooperation with the Community, evaluated the current facility and developed two recommended options, the first being to tear down and replace the existing facility with a new structure of similar size in the same spot. This facility would have a more convenient and marketable store layout fully utilizing the square footage of the facility, upgraded fuel pumps and point of sale systems, additional cooler space, and an array of new products. Store vendors also were evaluated and it was concluded that if the store changed its vendors then lower prices could be offered to community members.

Also to be considered was improving customer service through staff training, the use of weekly specials, providing a clean environment and shopping experience, and providing quality service to community members. The second recommended option to consider involved situating a new convenience store adjacent to the highway. This new facility would be unique in nature, as it would be constructed using an existing fire station, which would be converted into a full-service convenience store and gas station. The new facility would offer gas, diesel, and a larger selection of c-store products. This unique approach of renovating an existing structure saved the tribe substantially on construction costs instead of building a new one from scratch. It also brought a sense of community and culture to the facility, as there was a communal history associated with the structure.

As a result of the evaluation, the Tribe decided to build a new convenience store within a quarter mile of its existing gaming and hotel operations. This enabled it to cross-market using a player points system, which attracted additional customers. The facility was able to employ 13 more tribal members and provided lower costs to customers, a clean environment, and a variety of new product offerings to the community. The new facility provided more than $1 million per year in tax revenues and profits back to the Community. A portion of the profits were then used to rebuild the community grocery store.

Planning for Diversification: Isolated Tribes without Natural Resources

Using the framework Isolated Tribes with Natural Resources, discussed in the beginning of this section will provide most tribes some important food for thought regardless of their geographic locations and natural resource characteristics. However, the economic reality of some tribes features little in the way of natural resources and no meaningful access to a large population base. Tribes in this situation often have a traditional village or community located in a particularly isolated location as a result of various forced or unforced migrations dating back typically to the 19th century. In these cases, gaming in general, beyond that for local village, can be difficult let alone diversification.

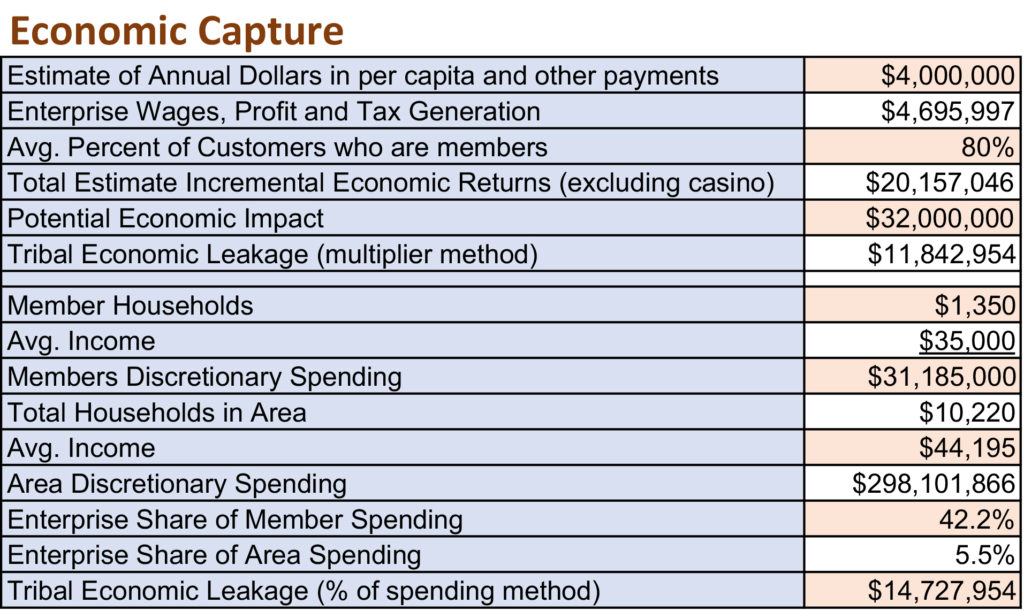

Tribes in this situation are often left with no choice but to consider purchasing urban or highway frontage acreage or pursuing off-reservation investments or economic development ventures. Some tribes have attempted to leverage their isolation and inherent notions of economic sovereignty into a vision for economic independence. This diversification model is founded on local economy principles and can be quantified in many situations. For example, working with the leadership of a Tribe in New Mexico.

For the purposes of investigating and planning for diversification, our selected example is focused on the Tribe’s capital town, as opposed to the broader reservation. This town has relatively little pass-through traffic, as it is cut off from major metropolitan areas by vast mountain ranges and accessible only via 85 miles of winding road. Home to roughly 2,600 people, this town is home to the only high school within one hundred square miles

The Tribe’s council had expressed an interest to Blue Stone in studying the town’s economic “leakage” – or the amount of dollars flowing out to businesses outside of the town – in an effort to understand how to diversify tribal revenues and provide more consumer goods and services to their residents. Viewed another way, The leadership wanted to position the Nation to capture more of the local spending power that the town possessed. Doing so would improve what is commonly referred to as the “multiplier effect” – where each dollar a community possesses is spent locally multiple times, thus maximizing that dollar’s local economic impact before it finally leaves the community. It also would provide a more diverse revenue base for the Nation in the form of taxes, rather than relying solely on the small casino and hotel in the center of town. This situation is common for rural isolated tribes, a twin desire to provide services and an amenity to members living on the reservation, and also to capture as much economic value internally, to be economically self-sustaining as much as possible. Taken a step further, it is a fundamental expression of economic sovereignty, the desire and effort to become less economically dependent on service providers outside the reservation, not just for funding government, but for tribal members who want to obtain consumer goods without having to hand over dollars to non-member businesses outside the reservation. We will explore the sovereignty aspect of this approach later in this book. For now, let’s take a closer look at their economy.

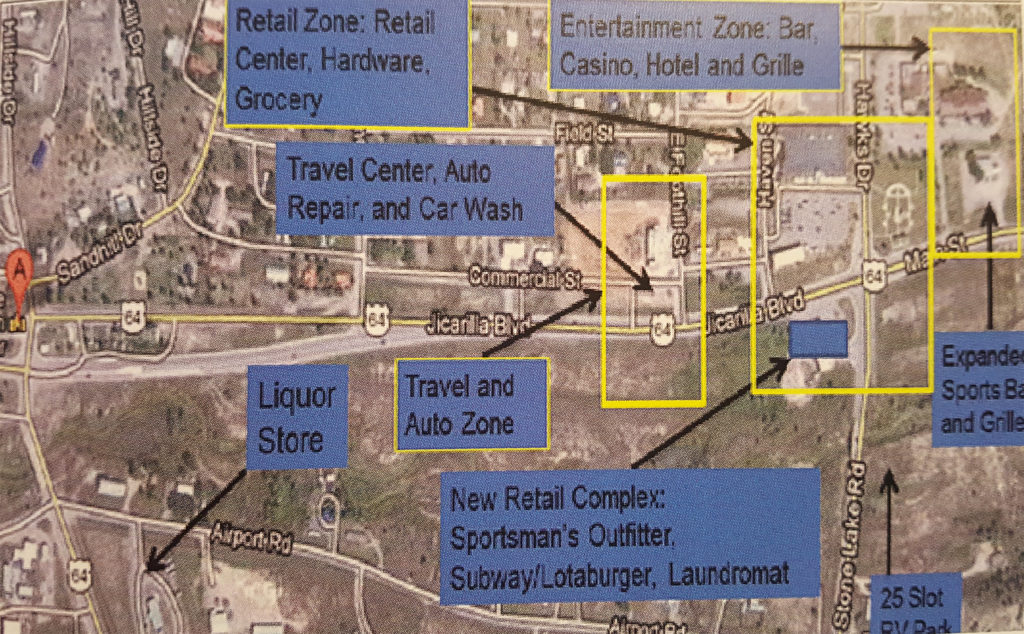

Using some basic assumptions based on demographics, the spending ability of residents can be defined in dollar amounts. Reviewing average income and net worth statistics from U.S. Census data, Blue Stone designed an analysis to estimate the percentage of household income that is spent locally and, conversely, the percentage spent outside of the community. Over the years, the leadership has gradually built up available goods and services by establishing enterprises to meet the identified needs of tribal members. The tribe operates a snack bar and dance hall, liquor store, auto repair shop, full-service grocery store, hardware store and two gas station/convenience stores.

Nearby entrepreneurs just outside the reservation and town boundaries operate a few restaurants and a dollar store that drains funds from the economy. More impactful, however, is the metropolitan area of Farmington, New Mexico, which pulls Tribal spending into fast food restaurants, a shopping mall, big box retailers such as Walmart, and movie theaters. Consider below the initial estimates outlining the impact of this ‘leakage’ of dollars into surrounding, non-tribal communities.

This analysis measures two different aspects of leakage or its opposite, ‘capture,’ to determine the dollars staying in the economy. Both methods assess only ‘regularly re-occurring’ spending, so one-time purchases such as automobiles, or large electronics (televisions, etc.) are excluded. The first method takes the per capita income of the community and compares that to the Nation’s existing business enterprises, adjusting for spending at the casino, and uses an economic multiplier to account for the times dollars turnover in the economy. The second method is more a bottom-up approach that takes the average income per household and compares that to the enterprise revenues to determine the percentage of dollars spent locally. While many different methods can be used for this analysis, the results of these two produced a range of between $11 and $14 million dollars leaking out of the economy annually. From a tribal government perspective, at an assumed 10 percent tribal tax rate, this means that the Nation misses out on $1.0 to $1.4 million a year in tax revenue. Additionally, the associated jobs lost to the economy outside of town is estimated at more than 100 jobs.

It is tempting in these situations for tribal leaders to work to capture every penny possible in the local tribal economy. In reality, it is important to understand that capturing near 100 percent of residents’ spending power simply isn’t realistic in the modern world.

It is tempting in these situations for tribal leaders to work to capture every penny possible in the local tribal economy. In reality, it is important to understand that capturing near 100 percent of residents’ spending power simply isn’t realistic in the modern world.

From internet sales to utility bills to federal taxes paid, there are only so many local dollars that a tribe can keep local, even under the best of circumstances. In this case, the tribe had already captured some of the biggest chunks of spending in the community: gasoline and food. Roughly 42 cents of every dollar was staying in the local economy. However, when surveyed, residents expressed a strong preference for “going into town” at least once a week to shop at the mall, dine at some of the restaurants, and see a movie in Farmington. It was more than a necessity; it had become a ritual that many residents carried out each week. Blue Stone worked with the Tribe’s leadership to understand how the economy could be further diversified to capture, or prevent the loss of, another 10 cents.

The analysis showed that retail was one of the main points of leakage, as was fast food. Car washes and ‘sports bar’-type entertainment were also activities that residents were currently spending money on outside the community. Using a general zoning principle, different areas of the town’s main street could be designed to facilitate spending in the local community. Blue Stone outlined the above map to highlight possible geographic combinations of enterprises that would encourage more local spending and provide natural buffers for culturally sensitive activities such as adult, night-life entertainment (including the casino), and day-time retail and car care enterprises.

To help infuse the economy with outside dollars, an expanded higher-end RV park was also assessed and located in an area where it would not interfere with residents’ retail activities. Taken as a whole, the analysis of the “leakage” provides a salient example of how rural isolated tribes can evaluate and plan for different economic diversification options.

To help infuse the economy with outside dollars, an expanded higher-end RV park was also assessed and located in an area where it would not interfere with residents’ retail activities. Taken as a whole, the analysis of the “leakage” provides a salient example of how rural isolated tribes can evaluate and plan for different economic diversification options.

In this section, we have broken down the first and perhaps most important step toward diversifying a tribal economy: Evaluating options and developing a plan. The various paths and options available to a tribe depend to a great degree on its geographic location and the natural resources it possesses. To help narrow down the various available options, it is helpful to divide tribes’ situations into a few categories with common characteristics. Tribes located near a large metropolitan area should begin by looking to diversification options that take advantage of their competitive advantage and existing capabilities.

In many situations, financial services and elective health care services can be good places to start for tribes already operating large resorts and casinos. For tribes in more rural locations but with access to a high-traffic corridor, capturing the spending power of travelers flowing through or near the reservation is an obvious first place to examine for pulling in outside dollars into the tribal economy. Rural tribes without this access can look to “exporting” their natural resources, if culturally appropriate, as a diversification tool.

Truly isolated tribes without natural resources can consider building strong local economies where dollars circulate between enterprises and the tribal village can provide diversification opportunities. Using these examples tribes can best evaluate and plan their own unique diversification program. In the subsequent chapters, we will move beyond the planning stage to discuss how to achieve diversification by using some unique tribal methods and leveraging some best practices from the corporate world.

“Many tribes have a lot of the same issues, but every tribe is still different. They have a unique location, a unique culture and a unique set of historical circumstances. Only the tribes themselves understand the best way to deal with that and economic development gives them the ability to address their own needs.” (Glen Gobin, Tulalip)